Making Peace in the Belly of the Beast

Both the limited-print edition of ONEING: Nonviolence and the downloadable PDF version are available now in our online bookstore.

There are many people who speak of American exceptionalism. They usually mean that America is not just one nation among many, but that God has a special destiny for America. Some contend our founding documents were inspired by God. Others say America has a unique role to play in the history of the world or the unfolding of biblical prophecy. That’s what they mean by American exceptionalism, but I think there is a different version: America’s exceptional reliance on violence.

WE HAVE A PROBLEM

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) called America “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” It’s not his most famous quote. It’s not on many MLK monuments or memes. You probably won’t hear it quoted by a politician on MLK Day, but the speech in which he gave it is golden:

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. . . . But they ask—and rightly so—what about Vietnam? They ask if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government.1

If that seems a little harsh or hyperbolic, consider this: The United States today has more guns than people, and we produce more guns than anyone in the world—9.5 million guns per year, 26,000 per day, one gun every three seconds.

We also lead the world when it comes to weapons of mass destruction. Of the 15,000 nuclear bombs in the world, 93 percent are owned by two countries, the USA and Russia. We have approximately 7,000 of them. Some of these bombs are 3,000 times stronger than Little Boy, the code name for the bomb used in Hiroshima. Our 7,000 nuclear bombs have the capacity of over 50,000 Hiroshima bombs.

Not only do we have the most weapons of mass destruction, we are also the world’s biggest arms dealer, boasting weapons contracts with over 150 countries. We export weapons around the world, sometimes to countries that are at war with each other, literally profiting off of death. And here is where we also are exceptional: We are the only country that has ever actually used a nuclear weapon—and we did it twice in one week.

When we conflate Christianity with nationalism, it does a lot of damage to the Christian faith.

Another unique marker of our penchant for violence is our use of the death penalty. The United States consistently makes the list of deadliest countries when it comes to executions. The United States is usually in the top five list of countries executing people, a list which also includes China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. The US is always in the top ten list alongside these countries and others that are not known for their commitment to life. In 1975, the year I was born, only fifteen countries had abolished the death penalty. Today, two-thirds of the world—over 150 countries—has abolished it. Only a handful of countries still carry out executions, and the US is one of them.

My point is not to attack the United States, but simply to say that we have a problem. We are addicted to violence—addicted. I’ve spent quite a bit of time in communities of folks recovering from addiction—and the first step of the 12 Step program is admitting that we have a problem. There are many other steps to recovery, including healing the harm that we’ve done, but we have to start with recognizing the harm we’ve done as a nation.

Dr. King was not wrong when he called America the greatest purveyor of violence in the world. We have a problem. We continue to trust in our chariots and our horses, our bombs and our guns. We continue to believe we can live by the sword but not die by the sword. We continue to choose vengeance over love as the force that will bring peace to the world. And, in the face of all that, we even have the pretention to call ourselves a “Christian” nation.

The word “Christian” means “Christlike,” and there are many things about America, in our past and in our present, that are not very Christlike at all. When we conflate Christianity with nationalism, it does a lot of damage to the Christian faith.

I think of the iconic words of Frederick Douglass (1818–1895):

Between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference—so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked. I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land. Indeed, I can see no reason, but the most deceitful one, for calling the religion of this land Christianity.2

We run the risk of inoculating people from Christianity. I use that word deliberately—especially since we are so familiar with vaccines these days. When we get a watered-down version of the disease, it builds antibodies and creates resistance to the disease. There is something similar with the watered-down version of American evangelicalism: It can inoculate people from authentic Christian faith.

In America, our money states, “In God We Trust,” but our economy looks like the seven deadly sins. We are very good at “taking the Lord’s name in vain”—breaking one of the big Ten Commandments. That isn’t just about yelling “God” when we stub our toe, but about carelessly using God as cover for our inaction, as justification for injustice. Over and over, we hear “God bless America,” even as many of our policies are crushing the people Jesus blessed in the Beatitudes.

In the end, the true test of our nation is how we care for the “least of these” (see Matthew 25:31–46). According to Jesus, every nation will be asked by God: When I was hungry, did you feed me? When I was a stranger, did you welcome me? When I was incarcerated, did you visit me?

BLESSED ARE THE PEACEMAKERS

So, what do we do? What does it look like to be a peacemaker in a world so full of violence?

I’ve heard my friend Richard Rohr say many times, “The best criticism of the bad is the practice of the better.” We’ve got to live out a better version of Christianity—one that looks more like Jesus, the Prince of Peace. It was Christ who said, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they are the children of God” (Matthew 5:9).

Nonviolence is not always our human instinct; we have to train ourselves in it. We’ve got to learn how to deescalate violence and interrupt it. We’ve got to tell the stories of peacemakers throughout history that can inspire us today.

We need new ways of praying that keep us rooted in nonviolence. Every day, I pray the fruit of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, gentleness, faithfulness, and self-control.

While all the books and resources are helpful, what we need today is not just more books—we need courage. We need imagination. We need to be as willing to die for the cross as people have been willing to die for the sword, or the gun, or the bomb. I have these powerful words on my desk, spoken by my friend Ron Sider back in 1984:

Unless we are prepared to risk injury and death in nonviolent opposition to the injustice our societies foster, we don’t dare even whisper another word about pacifism to our sisters and brothers in those desperate lands. Unless we are ready to die developing new nonviolent attempts to reduce international conflict, we should confess that we never really meant the cross was an alternative to the sword. Unless the majority of our people in nuclear nations are ready as congregations to risk social disapproval and government harassment in a clear call to live without nuclear weapons, we should sadly acknowledge that we have betrayed our peacemaking heritage. Making peace is as costly as waging war. Unless we are prepared to pay the cost of peacemaking, we have no right to claim the label or preach the message.3

These words helped to inspire the birth of Christian Peacemaker Teams, with whom I went to Iraq in March of 2003 (during the bombing of Baghdad).

Peacemaking is not just about the absence of conflict, but about the presence of justice. Dr. King even distinguished between the devil’s peace and God’s true peace. A counterfeit peace exists when people are pacified, distracted, or so beat up or tired of fighting that all seems calm. But real peace exists when there is justice, restoration, and forgiveness.

Peacemaking is about transforming the world from what it is into what God wants it to be.

Peacemaking doesn’t mean passivity. It is a deliberate act of interrupting injustice without mirroring injustice, the act of disarming evil without destroying the evildoer, the act of finding a third way that is neither fight nor flight, but the careful, arduous pursuit of reconciliation and justice. It is about a revolution of love that is big enough to set both the oppressed and the oppressors free.

Peacemaking is being able to recognize in the face of the oppressed our own face, and in the hands of the oppressors our own hands.

Peacemaking, like most beautiful things, begins small. Matthew 18 gives us a very clear process for approaching someone who has hurt or offended us: We are to first talk directly with them, not at them or around them.

But peacemaking is also about transforming the world from what it is into what God wants it to be.

GUNS INTO GARDEN TOOLS

Here’s one of the experiments in peacemaking I’ve been up to: turning guns into garden tools. Just over ten years ago, on the tenth anniversary of the September 11 attacks, I teamed up with my friend Ben Cohen (co-founder of Ben and Jerry’s Ice Cream) and we turned an AK-47 into a shovel and a rake. It was part of a spectacular event called “Jesus, Bombs, and Ice Cream” and was all about imagining a world with less violence . . . and more ice cream. For the finale, we dropped buckets of Ben & Jerry’s from the sky with helium balloons. It was a magical night, and we’ve been turning guns into garden tools ever since. There is now a national network called RAWTools (we get our name from flipping “WAR” around, and we are turning guns into garden tools all over the country).4

The whole movement is inspired by the biblical prophets who cast a vision of “beating swords into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks” (Isaiah 2:4). Together with my friend Mike Martin (co-author with me of Beating Guns: Hope for People Who Are Weary of Violence), we’ve travelled all over the country, visiting forty cities, transforming guns into garden tools, and centering the voices of those who have been impacted by violence.

Here is what I’ve realized during this time: We are not just protesting, we are protestifying. Every time we turn a gun into a garden tool, we are declaring that “all things can be made new” (2 Corinthians 5:17). Sometimes I hold up a shovel made from a gun and say, “This is what it looks like when a gun gets ‘born again.’” All things can be made new—metal that has been crafted to kill can be crafted to cultivate life. People can be made new. God’s love is powerful enough to change any human heart, no matter how hard it may be. Our policies can be made new too.

My friend Walter Brueggemann wrote a wonderful book called The Prophetic Imagination. In it, he suggests that we often misunderstand the prophets. Sometimes we think of the biblical prophets as fortune-tellers who are trying to predict the future. But that’s not quite it. The prophets were not fortune-tellers; they were truth-tellers. They were not trying to predict the future; they were trying to change the future, by awakening us to the present and inviting us to choose a different path than the tragic one we are choosing right now. We need that prophetic imagination today—that stubborn refusal to accept the world as it is and that insistence that another world is possible.

That iconic “swords to plowshares” passage ends by declaring “nation will not rise up against nation” and we will “study war no more.” But, according to the prophets, peace does not begin with kings or presidents or heads of state. They’re the ones who keep creating the wars. Peace begins with the people. It is not politicians who lead the way to peace; it is the people of God who lead the politicians to peace. The prophecy ends with the vision of a world free of violence, but it begins with us. The people get so fed up with violence that they take things into their own hands. They begin to transform their weapons into farm tools and, by doing so, they transform the world.

May it be so.

References:

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Beyond Vietnam,” (speech, Riverside Church, New York City, April 4, 1967), American Rhetoric Online Speech Bank, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkatimetobreaksilence.htm.

- Frederick Douglass, Life of an American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), Appendix, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/abolitn/abaufda14t.html.

- Ronald J. Sider, “God’s People Reconciling” (Mennonite World Conference, Strasbourg, France, summer 1984), as quoted in Shane Claiborne, The Irresistible Revolution, Updated and Expanded: Living as an Ordinary Radical (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2016), 197.

- To learn more, check out our website: www.RAWTools.org.

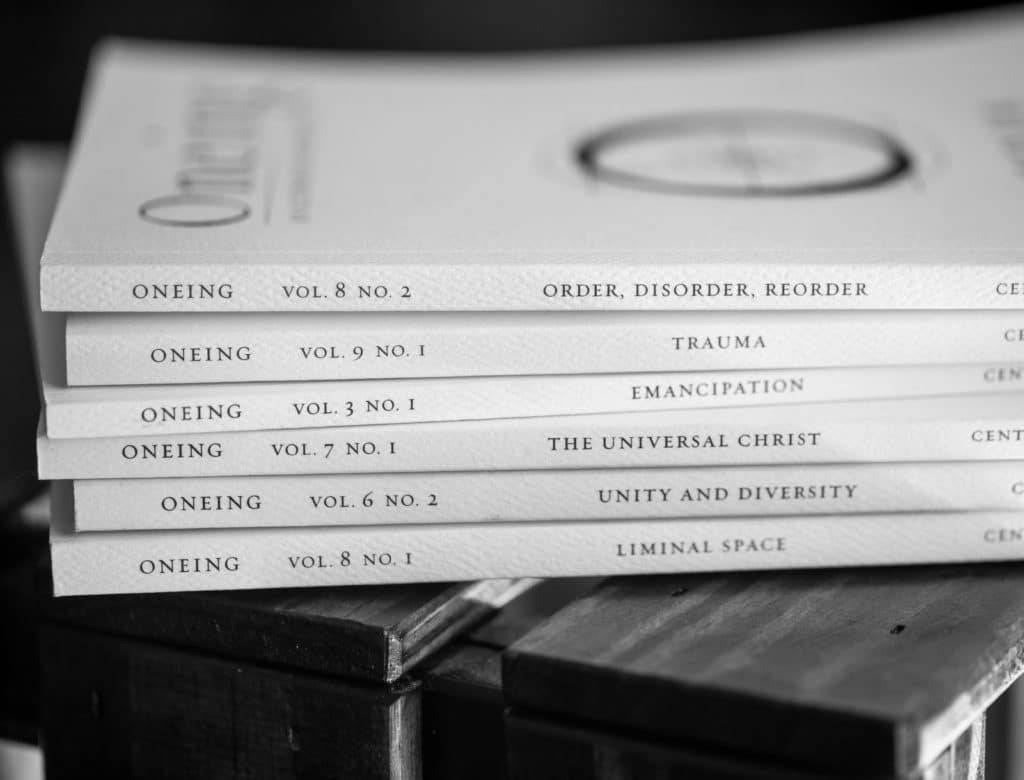

Established in 2013, ONEING is the biannual journal of the Center for Action and Contemplation. Renowned for its diverse and deep exploration of mysticism and culture, ONEING is grounded in Richard Rohr’s teachings and wisdom lineage. Each issue features a themed collection of thoughtfully curated essays and critical perspectives from spiritual teachers, activists, modern mystics, and prophets of all religions.